“The most reliable, flexible and effective form of target indication was, and still is, provided by the trained OP soldier operating deep in enemy territory.”

Major General ACP Stone CB

So said the founder of the “stay behind” Special OPs when we recorded a podcast with him in July 2020. This blog will discuss the training course and how volunteers were selected as Special Observers. I am grateful to several former colleagues for allowing me to use their photos and to former Troop Commander David Jones for providing me with source documents to draw from.

You can listen to our episode with the General here.

Formation Of The Unit

“The hunt was then on to select personnel with attributes that made them capable of working on their own or as part of a small team, behind enemy lines under arduous conditions.“

The idea of a Special OP Troop was developed in 1982. By February 1983 one troop was operational and under command of 5 Regiment RA based in Hildesheim. The original troop establishment was 36 all ranks, commanded by a Captain and included six, five-man patrols of which five were led by Subalterns. It was quickly realised that a Sergeant was capable of leading a patrol so the subalterns were removed from the order of battle.

In 1984 the depth fire concept, and move of Regiments to Dortmund, left 5 and 32 Regiments with a Special OP Troop each with the same establishment. Both merged in the late 1980s to form 4/73 (Sphinx) Special OP Battery Royal Artillery and the unit still exists today as the Army’s long range recce patrols unit. The Regiments were equipped with the M107 gun and later MLRS giving the patrols the range to strike the enemy.

The hunt was then on to select personnel with attributes that made them capable of working on their own or as part of a small team, behind enemy lines under arduous conditions. General Stone remembers “What I thought we needed was completely concealed OPs deployed right up against the IGB and allowing the advancing enemy army to pass over them so that they were then right in amongst the enemy tanks and could, with extreme accuracy, direct artillery fire onto them as well. Of course, as to themselves, it’s almost a suicide mission and that would require some pretty special OPs indeed. Survivability was obviously the key issue, and this could only be achieved by having OPs dug in underground along the IGB and in depth behind the forward OPs.“

This radical suggestion, at the height of the Cold War, was pushed through by the persuasive General. After constructing a coherent argument on paper, he presented it to the Corps Commander General Sir Nigel Bagnall GCB, CVO, MC. The General recalls how the meeting went “He was a fiery red headed cavalryman. He had a very, very short fuse. And I was sent for and he pulled me into the office. No coffee but a fairly intense interview and quite a lot of questions. But he thought the idea was sound. And in the end, much to my surprise, he simply said, right, get on with it. So, there it was. He didn’t consult his staff. He didn’t have the paper sent round to be discussed with anybody. He said, get on with it. So that’s what we did.”

The British Army has a long history of determined men forming specialist units against the odds. The General was about to add another to the Army’s order of battle.

Designing The Selection And Training Course

“In essence volunteers needed to have the often elusive combination of fitness and intelligence underpinned by common sense.“

General Stone knew the qualities for a Special Observer would be different as he made clear in the podcast we recorded with him.

“Well, the qualities that I believe volunteers would need and all of them, incidentally, had to be fully trained soldiers with some experience under their belt before they started…were first and foremost absolute dedication, a commitment to the task that that wouldn’t falter then determination and self-belief. You’ve got to really understand what you’re capable of and what you’re not capable of. But self-belief is very important. The ability to work in a small and close-knit team and recognising that the expertise was shared across the team and not necessarily held by every member. So, you needed mutual respect in each other’s ability, regardless of rank. It must be quite clear by the commander of a six-man patrol that his most junior soldier might have some particular skill which none of the others had. And so great respect had to be acknowledged for the skill that that individual might have, and then a professionalism that guaranteed self-discipline of the highest standard.”

In essence volunteers needed to have the often elusive combination of fitness and intelligence underpinned by common sense. It’s important to note that, though a decent standard of fitness was required, much of their capability came not from physical prowess but from a specific mindset. This was in evidence in later years when, as the organisation matured, it turned out Warrant Officers way in excess of its establishment.

In 1982 there were other specialist units running courses for the British Army. These included the Commando Brigade and, in Special Forces, 14 Intelligence Company and 22 SAS. All ran well known if vastly different selections. It was to these units he turned to devise a programme for picking Special Observers.

Initially all volunteers were expected to come from the ranks of the Royal Artillery so getting the required numbers was going to be a challenge. The General takes up the story “… it was a major problem, therefore, working out how to do this and it was never clear with whom I could seek advice. So I started, first of all, to go to all three centres of excellence for Special Forces. I started with Hereford, where I witnessed a selection course there or part of it and how they did it. And they told me all about what they were looking for. I then went to the Lympstone to the Marines and went through a similar exercise and finally to the Paras in Aldershot, of which I had some experience through my own time in airborne forces. And I studied each of their methods of selection. And I eventually focused on adapting to have a selection course, which was most likely to produce the sort of soldiers that I was looking for. That said they all had something to offer, and so I thought it useful to get permanent staff instructors (PSI) from the SAS, from the Royal Marines and from the Paras to run selection courses for us”.

In the end the initial cadre of instructors included not only SAS, and Parachute Regiment but also 14 Intelligence Company, responsible for surveillance tasks in Northern Ireland, and 148 Commando (Meiktila) Forward Observation Battery tasked with Naval Gunfire Support to 3 Commando Brigade.

Geordie Lillico & Willie McCracken

Two of the instructors reputations preceded them before arriving in Dortmund in the form of Geordie Lillico and Willie McCracken. It’s worth taking time to recount why they were held in such high regard.

“Sergeant Lillico throughout this action displayed the finest leadership, bravery and self-sacrifice.“

“Eddie ‘Geordie’ Lillico was a long serving soldier in 22 SAS who was awarded the British Empire Medal and the Military Medal for an incident in the Borneo campaign. His bravery and leadership are made clear in his citation.

“Sergeant Lillico was in command of a Special Air Service patrol engaged in border surveillance on the Indonesian/Sarawak frontier. On the morning of 28th February, the patrol was moving through jungle when they made head on contact with a party of enemy. The enemy opened fire immediately, and both Trooper Thomson and Sergeant Lillico, the lead scout and second man respectively, were both badly wounded.

They returned the fire, killing two Indonesians. Lillico then ordered Thomson, who he thought could crawl, to get back to the emergency rendezvous. He himself could hardly move as his leg was paralysed by the wound, but managed to drag himself out of the immediate contact area into some bamboo cover where he lost consciousness. He remained in this position till the following morning when he dragged himself some 4-500 yards to the top of a near-by ridge where he hid. Shortly after he reached this area he heard a helicopter and switched on his Sarbe beacon to attract its attention. At the same time he realised he was very close to the enemy, as he heard and saw Indonesian soldiers, and on the approach of the helicopter one of the enemy climbed a tree some 40 yards away from him to look around.

Sergeant Lillico, realising that his beacon signal would bring the helicopter within reach of the enemy, switched it off in order not to endanger the aeroplane. He afterwards crawled away from, this position some little way. Later that day the helicopter returned, and this time Lillico considered he was sufficiently far from the enemy not to endanger it and again switched his beacon on and succeeded in bringing it to his position. He was then located and winched out.

Sergeant Lillico throughout this action displayed the finest leadership, bravery and self-sacrifice. He showed superb presence of mind and courage, when badly wounded, in switching off his Sarbe beacon when within close enemy range, and thereby most probably avoided the loss of a helicopter and its crew. This is the more remarkable in that at this time he had been wounded for over 24 hours and had lost a considerable amount of blood.”

“Captain McCracken’s high courage and professional skill were in the highest tradition of the Royal Artillery.”

Willie McCracken was a Royal Artillery officer who had served in 148 Bty and won an MC during the Falklands War in 1982. His citation for the award states.

“Captain McCracken, 29 Commando Regiment Royal Artillery, was in command of an Artillery and Naval Gunfire Forward Observation Party grouped with B Company 3rd Battalion Parachute Regiment during the period 13-14 June 1982. During the attack on Mount Longdon in the early hours of 12 June Captain McCracken consistently brought down artillery and naval gunfire safely in very close proximity to his own troops allowing them to manoeuvre whilst still maintaining contact with the enemy. Throughout this period he and his party were continually under heavy enemy small arms, mortar and artillery fire. Much of the time the Company Headquarters with which Captain McCracken and his party were co-located were involved in the small arms fire fight and in this fire fight Captain McCracken made a significant personal contribution, accounting for several enemy dead.

Captain McCracken showed outstanding personal courage whilst carrying out his duties in a most professional, calm and competent manner. His control of artillery and naval gunfire undoubtedly accounted for many enemy casualties and greatly assisted in minimising our own. His determination, professionalism and courage were an example to all. Always in the thick of the fight, he made a significant personal contribution to the success of the mission and to the minimising of casualties to the Battalion.

During the night of 14 June Captain McCracken and his party were regrouped with 2nd Battalion The Parachute Regiment for their attack on Wireless Ridge. Throughout this attack Captain McCracken was sited in an exposed OP position on Mount Longdon. Under constant enemy mortar and artillery bombardment Captain McCracken continued to bring down accurate and effective naval fire. This fire resulted in the successful neutralisation of at least one company objective and the harassment of enemy gun positions. The application of indirect fire played a major part in the success of the Battalion’s attack, the minimising of our own casualties and the eventual surrender of the enemy. Captain McCracken’s high courage and professional skill were in the highest tradition of the Royal Artillery.”

It was men like this who helped influence the training of Special Observers. Over the next two decades Chief Instructors would be seconded from the Parachute Regiment and later 22 SAS to run the selection course. This relationship with Hereford ended in the early 2000s when commitments to the global war on terror meant the Regiment could no longer provide personnel.

The Special Observer Course

“… it is the eyes, the ears, the experience and the instant decision-making ability of a specially trained OP soldier that is second to none in the process of high-quality surveillance and target decisions…”

Major General ACP Stone CB

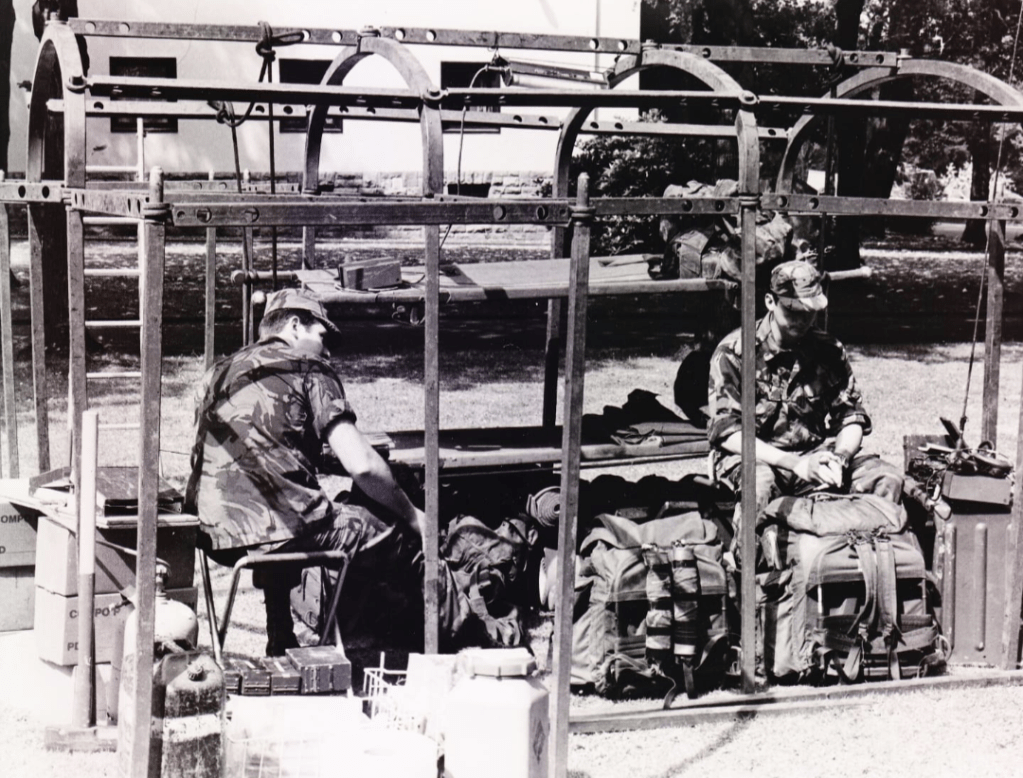

Training would be divided in two parts. First an initial selection of 7 days carried out in the field was followed by a 19-week continuation phase to teach soldiers the skills needed to function in stay behind OP patrols. Continuation training would be broken down into skills packages such as field firing, recognition and communications and would be a mix of classroom and field exercises. The final exercise would see soldiers deploy in a mexe hide for 3 weeks to practice a full deployment in role.

You can listen to our podcast about the early selection course with Iain Strachan below.

Initial Selection

The aim of selection was to allow volunteers the opportunity to demonstrate their potential, so testing was limited to subjects taught during the selection period or during basic training. It was not designed to mirror the physical requirements of the parachute or commando courses as the qualities required of a potential Special Observer were particular to the role. Candidates were given joining instructions and a report date to assemble at the barracks of 5 Regiment RA in Dortmund on the Sunday prior to the course starting. Once booked in they were given several days rations and a set of maps for the week. The selection programme was broken down as follows:

- Day 1. Arrival. Students are shown the film “The Sniper” which demonstrates the construction of a sub-surface hide similar to those used by the OP Troop. Each volunteer then gives a short talk about their background as an “ice breaker”.

- Day 2. The CO gave an opening brief which was followed by a Basic Fitness Test which was standard in the Army at that time. Students were then loaded on trucks with all their equipment and weapons to be transported to Hildesheim, later Hagen, where the selection training rea was located. On arrival they were split into 4-man patrols and occupied a tactical troop position. Within the patrol each soldier was given a partner who had to remain within 2m distance at all times. Selection instruction and lessons were conducted around a central tented “schoolhouse”. The remainder of the day was taken up with instruction followed by an overnight patrolling and recce task. 16 hours were allocated for this.

- Day 3. Patrols wrote and handed in their reports which had to be ready by lunch time. this was followed by a syndicate appreciation and a battle run with weapons. After a late evening meal, the students were allocated admin time and left alone, less sentry duty, until early the following morning.

- Day 4. This day was taken up by an individual navigation exercise with weapons and belt kit which took about 9 hours to complete.

- Day 5. This started with a battle run of 8 km with weapons then milling, a form of boxing, which was a test of controlled aggression, determination and confidence. This was followed by abseiling, observation tests and a general military knowledge exam. Late that evening a visit to a small 40m long tunnel was conducted to eliminate those who were claustrophobic. on return to the harbour area normal routine was continued.

- Day 6. After breakfast students carried out weapon handling tests. Orders were then issued for the final phase of the selection process, the OP exercise. At last light patrols deployed to their allocated areas where they conducted a recce and occupation of OPs. By this time on my course over 50% of students had dropped out and my patrol comprised me and one other person.

- Day 7. The final day, up to late afternoon, was taken up by OP routine and DS initiated sightings which had to be logged in a book. This was checked for accuracy at the end of the exercise. No signals training was conducted during the selection period therefore no radios were used during this phase. OPs were then attacked, and soldiers had to escape to an ERV where they were loaded in trucks and driven around for several hours in order to disorientate them and make sleep difficult. When the trucks stopped students were ushered off and had to conduct a timed march of 10 miles with rifle and belt kit. At the end of the march a “sickener” element was included where soldiers were told to prepare themselves to do the route once more in reverse order. On my selection this resulted in two of the remaining 5 dropping out. However about 2 miles down the road there was a truck waiting and the test was over.

Those remaining returned to Dortmund where they were marched into the training team office for a debrief. If successful they were given a reporting date for the next phase and sent back to their units. A few things stick in my memory after nearly forty years. Firstly, the appearance and professionalism of the DS who all looked fit and exuded confidence. Second, there was no shouting or drama. Everything was done in a calm but controlled manner and you were expected to get on with a task with minimal direction. When I marched out the office, I was met by a member of the DS who took me and the other successful applicant up to the bar in the unit lines where were given a couple of beers before transport took us back to our regiments. Those last points, more than anything else, made me realise this was the organisation I wanted to belong to and was what I imagined the Army would be like.

Continuation Training

Continuation training taught students the baseline skills required to join a patrol. It was both demanding and thorough culminating in a final Exercise called Test Bed. This was a 3-week mexe shelter exercise from digging in, occupation and exfiltration practising all the patrol skills learned over the last few months. Where possible, this was run as part of a larger exercise such as Reforger in 1987. On completion of this phase students were qualified as Special Observers (basic) and posted to the OP Troop of either 5 or 32 Regiment. With regards to soldiers passing the course the failure rate in 1988 was 60%. However, many students withdrew themselves usually because they did not want to be employed in a role so field orientated. The course was broken down as follows:

Phase 1.

- Week 1. Signals. Basic signals with PRC 319/320. Use of OTP code book. Included Ex Radio Walk (36 hrs). This involved navigating check point to check point in pairs with full equipment and weapon carrying out signal exercises.

- Week 2. Infantry skills. Basic battle drills and fieldcraft.

- Week 3. Exercise Ground Hogg. Map reading theory and practical. Winterberg area.

- Week 4. Tactics. Patrol and Troop level theory and practical. Includes Ex First Try (36hrs).

- Week 5. NBC and First Aid. Practical and theory.

- Week 6. Weapons training and survival. Includes Exercise Semi Rough (36 hr) survival exercise living off belt kit.

- Week 7. Ex Ultimate Aim. Hasty option surface OP exercise. Deploy immediately after survival exercise.

- Week 8. Exercise Night Shift. Night patrolling exercise to include CTR, ambush etc.

- Week 9. Exercise Last Straw. Final exercise of phase 1 where all aspects of training were tested.

Phase 2.

- Week 10. Advanced HF signals training. To include morse and use of DMHD burst transmission device. All basic qualified patrol members had to be capable of 8 words per minute for advanced qualification 12 words per minute was required.

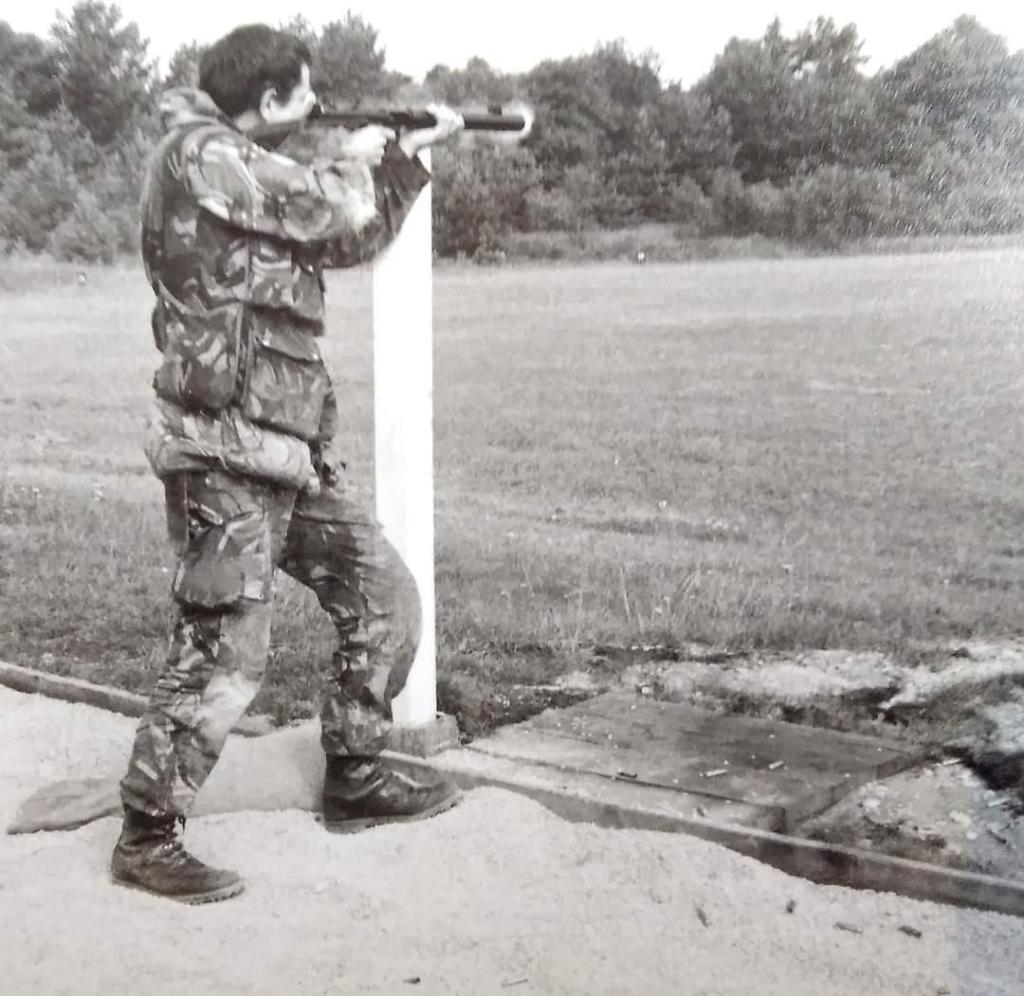

- Week 11. Field firing. Individual building up to patrol. Contact and OP breakout drills. Using all weapon systems to include SLR, 9mm Browning and suppressed SMG.

- Week 12. Hospital week. Advanced first aid at a British military hospital.

- Week 13. Observation Post assistant. At the end of this week all students were capable of directing artillery fire. Later they would have to attend a 4 week formal basic course in order to gain a qualification.

- Week 14. Exercise Test Bed. A 3 week full mexe deployment including exfiltration.

During phase 1 and 2 when in camp PT was conducted every day likewise Soviet vehicle recognition and tactics. In phase 2 morse was practiced as formal lessons when not in the field.

Advanced Training

To qualify to advanced level soldiers had to pass a Survival With 24 hrs Resistance To Interrogation course as Special Observers were classed as “prone to capture” troops. In addition, a Warsaw Pact Specialist Recognition course had to be passed. Both were two weeks long and were held at the International Long Range Recce Patrol School in Weingarten.

Further Training

Completion of this training enabled a soldier to have the required skills to be a useful team member. This wasn’t the end of the journey however as many other courses would have to be completed in order to ensure that skills were honed or added to. Some examples are listed below using the language of the time.

Royal Artillery Courses.

- Observation Post assistant to detachment commander level.

- Signals to detachment commander level.

- Forward Observation Officer.

- Targetting.

Army Courses.

- Junior/Senior Brecon.

- FAC.

- Skill at Arms instructor.

- Jungle warfare instructor.

- Arctic warfare.

- Prisoner handling and tactical questioning instructor.

- Conduct after capture instructor.

- Field firing 4 and 5.

- Army combat survival instructor. This was run at Hereford and was required for promotion to sergeant. It also meant another 24 hrs practical resistance to interrogation training.

International Long Range Recce Patrol School.

- CQB.

- Ops planning.

- Patrol medic.

- Patrol leaders.

- Winter patrol.

One Soldier’s Story

If you want to know more about the role, selection and training of special observers in the “stay behind” role during the Cold War you can listen to my guest slot on the Cold war conversations via the link below:

The Final Word

I will finish with a comment from General Stone at the end of our podcast regarding the future of Special Observers.

“Suffice to say that I think the important point to make is that it is the eyes, the ears, the experience and the instant decision-making ability of a specially trained OP soldier that is second to none in the process of high-quality surveillance and target decisions. This man in the loop and not a man in the loop on a radio or on some vision equipment through a UAV, but somebody who’s actually there on the ground. Real time intelligence and accurate identification provided by soldiers are vital if you want surveillance missions and precision targets to be carried out properly.

And certainly, while collateral damage is to be avoided, even modern technology can’t be relied on to achieve that. In warfare, which today is conducted within areas filled with non-combatant personnel, you need the man on the ground very, very close to the action. And as I say, the required results can only really be achieved by soldiers who are able to carry out that role while deployed very close to their targets and are able, with eyes on, to prosecute or abort their mission at the very last minute.

And it follows, as I see it, that Special OPs will remain very much in demand for a wide range of extremely difficult and unconventional missions for the foreseeable future. And I wish them well.”

Copyright © 2022. All rights reserved by the author Colin Ferguson. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing of the author.

A very interesting read. Thank you Colin.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Russel.

LikeLike

Great, well put together by the author. I admit I know him pretty well as we have served on operations together, often sharing a sleeping bag.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I still have nightmares about that Bren!!

LikeLiked by 1 person