Several years ago I was reading an item on the popular TV show “Who Do You Think You Are?” In it a producer said that often the celebrity whose family they were researching had nothing noteworthy in their history as most of our ancestors faced a life of unremarkable graft and hardship. Fortunately my own family genealogy has revealed a story that would suit prime time TV.

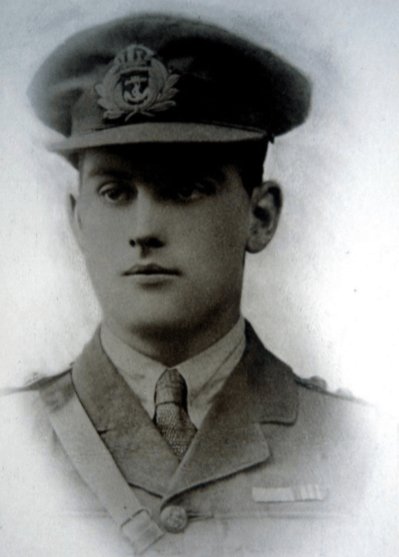

During my research I was in touch with my mother’s cousin Ottilia Saxl who discovered a great uncle who fought in the First World War and was in all three branches of the services. In addition he won the Military Medal (MM) as an Acting Sergeant in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers Regiment and the Military Cross (MC) as a Sub Lieutenant in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). Though he survived Gallipoli and the trenches John Miller Coutts Weir died of blackwater fever, a complication of malaria, 3 years after the war ended in Sapele, Nigeria while working in the mahogany timber industry.

Early Life

John was born the son of a Master Saddler in Selkirk in 1893. Aged 16 he left school to become an insurance clerk with the Commercial Union Assurance Company in Edinburgh. On 4 August 1914 the United Kingdom declared war on Germany as a result of their refusal to remove troops from neutral Belgium. The war that was expected to be over by Christmas continued into the New Year and John volunteered to serve with the KOSB that January.

With The KOSB – Gallipoli 1915

“Come away, Borderers! Don’t be beaten!”

Captain A. Wallace 12 July 1915.

John first saw active service in the Dardanelles where he deployed on 30 June 1915. This followed the assault on the Gallipoli Peninsula (Gelibolu in Turkey today) the previous April by British, French and ANZAC troops. The aim of the campaign was to take command of the Ottoman Straights and control the sea route from Europe to Russia. Poor intelligence, difficult terrain and a determined Turkish defence led to heavy casualties amongst the allies with 46000 killed. Turkish deaths were an estimated 65000 killed. Due to these difficulties the British government ordered a withdrawal which was complete by 9 January 1916.

The KOSB paid a heavy price during the campaign and it’s likely John saw more than his fair share of fighting. One battle at Helles on 12 July 1915 had two Battalions from the Regiment involved in an attempted break out. The CO of 1/5 KOSB wrote in the Battalion war diary:

“Within 150 yards the charge became a walk but there was no wavering. The 1/4th R.S.F. and the French failed to advance beyond the line of the 1st Turkish trench. Hence the 1/4th K.O.S.B. was absolutely in the air, as also was the right of my leading (the third) wave. The first two waves (1/4th K.O.S.B.) failed to find any trace of the objective assigned to them. A certain number returned on my right but about 300 officers and men are still missing and unaccounted for. The 3rd wave was gradually bombed towards our left until a party of about 40 men under Lieut. Douglas was left. In spite of all efforts to dislodge him, Lieut. Douglas held on until reinforced, when the line was made good. The 1st Turkish trench was captured at once, consolidated and held.” [1]

One account described the price paid by the officers encouraging their soldiers forward:

“Come away, Borderers! Don’t be beaten!” was the stirring cry of Captain A. Wallace as he continued to advance, although badly wounded and with blood streaming down his face, until he was hit again, this time to fall a dying man. Lieut. J.B. Innes had one of his arms shattered by a bursting shell. He got his cousin, Lieut. W.K. Innes, to cut it off, asked for a cigarette, and continued to cheer the Borderers on until he died from loss of blood.“ [2]

At the close of roll call 1/4th KOSB suffered 535 casualties and 1/5th a further 270. [3] John left the Dardanelles on 10 October 1915 though his service records do not indicate the reason for his posting.

With The KOSB – France 1916 To 1917

“acts of gallantry and devotion to duty under fire”

Requirement for the award of the MM.

Back in Europe John served with 6th Bn KOSB in France from February 1916 to January 1917 at a time when the Regiment was involved in intense fighting at the Somme . It is possible he was a casualty replacement after the Bn had suffered heavy casualties at Loos in September 1915. This was the battle in which the late Queen Mother’s brother, Captain The Hon. Fergus Bowes-Lyon, was killed while serving with the Black Watch. Coincidentally he’s commemorated on my village war memorial alongside other local men. On the 22 January 1917 as an Acting Sergeant John was won the MM which, at that time, was awarded to other ranks for “acts of gallantry and devotion to duty under fire”. Unfortunately no records exist for WW1 MM citations as they were destroyed during the London Blitz.

Commissioned In The Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve 1917 To 1918

John’s courage, steadyness under fire and leadership abilities must have impressed his superiors. On the 27 June 1917 he was transferred to the Navy and commissioned as a Sub Lieutenant in the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division which had been raised at the start of the war from RM and RN personnel not required at sea. In 1916 after heavy casualties it transferred to the Army fighting on the Western Front until the Armistice. Ottilia takes up the story:

“In October 1917 the 63rd Division moved north to the salient where Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) was in full swing. There are graphic descriptions of the conditions and the fighting during the attack on Passchendaele alongside the Canadians on 30th October which cost the battalion 350 casualties. Two months later, more fierce fighting at Welsh Ridge took place following the German successful counter-attack at Cambrai, and again in the early days of the German March offensive of 1918. On the 17th November 1917, John Weir is recorded as ‘embarking Folkestone, disembarking Boulogne’ where he joined the base depot at Calais, presumably on his way to the action at Cambrai, and thence to Welsh Ridge, where his courageous efforts result in the award of a Military Cross.” [4]

Battle Of Welsh Ridge

Welsh Ridge was a prominent feature captured during the Cambrai battle and the British units, RM and RNVR, manned trenches forming part of the Hindenberg Line. A dawn artillery barrage preceded a determined attack by German storm troopers, camouflaged in snow suits, who had moved forward using the bombardment as cover. Vicious close quarter fighting ensued with the British taking heavy casualties before relief came in the form of a counter attack by the Nelson Bn and Artists’ Rifles subsequently reinforced by the Anson Bn. Two days of fighting saw the Division suffer 1420 casualties but the ridge was held and 15 enemy Bns defeated.

Edinburgh Gazette MC Announcement 19 August 1918

“In spite of the intense barrage he kept his remaining men together & fought every inch of ground. Although he had his revolver blown out of his hand he remained unshaken & threw bombs at the

Hood Battalion citation.

enemy.“

“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. When the enemy attacked after an intense bombardment and penetrated part of his line, he kept his men well in hand and fought every inch of ground. He led a counter-attack, drove the enemy back to their own lines, and reorganised the position. He held his ground against several further attacks under heavy fire, and inspired his men throughout by his determined and courageous leadership.“ [5]

The Hood Bn write up contains further detail:

“On 30th Dec. 1917, in the attack on WELSH RIDGE, when the enemy with his storm-troops pierced part of our line, this officer showed great gallantry in leading his men. In spite of the intense barrage he kept his remaining men together & fought every inch of ground. Although he had his revolver blown out of his hand he remained unshaken & threw bombs at the enemy. He went back for reinforcements & more bombs & organised a bombing party to push back the enemy. It was mainly owing to his leadership & organisation that the enemy were forced to withdraw. He forced the enemy right out of the sap & back to their own lines & reorganised men to hold the sap. During the next 48 hours, when the enemy attacked on several occasions after heavy artillery preparation, he displayed great courage & coolness throughout the whole period, helping & encouraging his men the whole time. He came out of action with 8 men only.” [6]

Wounding And Return To England

In April 1918 John was promoted to Lieutenant but his luck finally ran out when he was shot in the left elbow. Three days later he returned by hospital ship to England.

Ottilia’s research discovered more about his rehab:

“On April 22nd, John Weir was admitted to the 3rd Southern General Hospital in Oxford. On the 1st May he was assessed by a Medical Board, and deemed unfit for active service for 2 months. Now out of action, his Hood Battalion record states he ‘relinquishes the pay of acting rank of Lieut RNVR as he has ceased to command a Company’, but nonetheless he retains his rank, and is entitled to wear the badges of that rank. On the 16th May, after only a fortnight, the Medical Board surprisingly pronounced John ‘fit for general service’ and grant him three weeks leave, before rejoining the 2nd Reserve Battalion at Aldershot on 7th June – which he duly does.” [7]

With The RAF

Shortly after this John decides to make an application to join the RAF which became the third service on 1 April 1918 being formed from the Royal Flying Corps. While waiting for his application to be approved he is kept busy including a rifle qualification course, draft conducting duty in France and a 4 day Gas course. I attended a similar course, now 3 weeks long, in the 1980s the Nuclear, Biological and Chemical (NBC) Warfare Instructors course. I get the impression John was an indifferent student being assessed as “…unlikely to make a good anti-gas instructor”. [8]

His application for the RAF is accepted and on 24 August 1918 he reports to the Aeronautical College at No. 1 Officer’s School at Brocton Camp in Staffordshire. From Ottilia’s research we discover that:

“He is there until the 19th October, where he obtains a ‘satisfactory report’. By the 28th October, John is noted as going to the School of Aeronautics, RAF Reading. His record then reads: “Taken on strength from 2nd Reserve Battalion. 05.11.18, whilst attached RAF Reading”. He continues at the Aeronautical College until 3rd March 1919.” [9]

By now the “war to end all wars” is over and perhaps John is losing interest in service life. Ottilia makes an interesting observation:

“He doesn’t seem to have set the heather on fire as a potential pilot, but maybe as someone who has seen so much action he doesn’t suffer others telling him what to do. Who knows?? I get the feeling that for most of 1918, John Weir’s superiors are being kind to him, by sending him on courses and less dangerous assignments. Maybe they recognised that he had spent nearly three

years in the worst theatres of the First World War and had acquitted himself well – and your luck can run out. Maybe that is just wishful thinking.”

Demobilisation And Post Service Life

Away from the dangers of the front line John enjoys life much like any other young man. Unfortunately he contracts an STI and on 31 March 1919 is treated at a military in hospital in Newcastle and medically down graded for two months before being discharged on 28 May 1919. John reports back to his Army Bn and is demobbed from the service on 06 June 1919.

For this twice decorated former Navy officer, who had fought numerous battles in some of the hardest theatre of operations in a world war returning to life in an office wasn’t an option. Just two months later he sailed from Liverpool to Africa and a new career as mahogany timber trader in the jungle forests of Nigeria.

Working in Nigeria wasn’t without its own dangers. This time the threat wasn’t bombs, bullets or poison gas but endemic diseases such malaria and typhoid. On 15 April 1921 John died of Black Water fever at the age of 28. A tragic end for someone who had survived the privations and dangers of the Great War.

Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved by the author Colin Ferguson. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing of the author.

References:

- [1] KOSB website https://www.kosb.co.uk/12th-of-july-1915-gallipoli/

- [2] KOSB ibid.

- [3] KOSB ibid.

- [4] The Story of John Miller Coutts Weir, M.M., M.C by Ottilia Saxl.

- [5] Saxl ibid.

- [6] Saxl ibid.

- [7] Saxl ibid.

- [8] Saxl ibid.

- [9] Saxl ibid.