By Kim Read

Introduction

In my previous blog I covered my experiences on the ILRRPS Warsaw Pact Specialist Recognition, Battle Field Survival and Escape and Evasion Courses.

This follow up will cover the subsequent training I undertook.

- Patrols Course.

- Patrol Leaders Course.

- Patrol Medics Course.

- Close Quarter Battle Course

As previously stated , the training was constantly being improved and adapted. So other students may remember their courses running differently. I attended the school between 1984-88. Any opinions and observations are my own and the experiences are written to the best of my memory. A list of abbreviations can be found at the end of the blog.

You can listen to the podcast I recorded for the Unconventional Soldier podcast about the ILRRP school via the Spotify link below.

ILRRPS Patrol Course

“Above all, next to valour the best quality in a military man are vigilance and caution.”

– Major General James Wolfe 1759 Quebec campaign.

“Patrol” was the term given to a group of soldiers assigned a particular task or mission. The size of a patrol could depend on the task, but for us, patrol size was usually between 4 or 6 men. This gave us the greatest flexibility in deploying personnel for observation posts on the ground. The patrol would consist of the Patrol Commander, usually a Sergeant, though depending on task, a Bombardier /Corporal was not unknown. The patrol would also have a designated Signaler, Medic and German speaker. Cross training within the patrol was vital, especially for communications and all members could establish radio contact, select appropriate antenna configurations, code/decode messages. Every patrol member knew how to treat wounds, establish an airway and adminster IV fluids for a casualty. Specialist equipment, observation devices, spare radio batteries and OP construction equipment were spread out between the members.

Standards varied hugely across other NATO Armys at the time. It must be remembered that many countries within NATO relied on conscription for the bulk of their soldiers. Not every nation practiced cross training within their units. This was often due to budget restraints or to the limited time conscripts served. That said most nations staffed their specialist units with volunteer or professional soldiers. The courses at ILRRPS were designed to help standardise procedures and improve the skills of NATO soldiers who were involved in long range reconnaissance tasks.

Reconnaissance is vital for any commander preparing for an operation. The more information you had about “what is going on on the other side of the hill” as the Duke of Wellington put it, the greater the chance of success. The infantry carried out mainly reconnaissance by foot, probing the ground ahead of their positions and behind the immediate front line. For more in depth longer range reconnaissance, traditionally cavalry was used and later light armoured vehicles. They could cover more ground and extract themselves faster if danger threatened.

In World War II we started to see the use of long range reconnaissance being used in all theatres of war. The more rugged the terrain, the more likely this was to be used to the advantage of long range reconnaissance units. The Long Range Desert Group, a motorised unit formed mainly to gather intelligence deep behind the lines of the Afrika Korps had great success in the deserts of North Africa. In the Russian- Finnish conflict, the dense forests provided perfect cover for stay behind units of Finnish ‘Sissi’ Light Infantry who gathered information and carried out raids and ambushes behind Russian lines. The jungles of the Far East saw several units formed such as the Australian Z Special Commmando group who operated amongst the multitude of islands of East Timor and Malaysia to carry out intelligence gathering and raids on the Japanese Forces.

Post war conflicts in Malaysia, Borneo, Vietnam, Rhodesia and the Middle East saw the rise of counter insurgency warfare. This elusive enemy was often best tackled with unconventional LRRP type units who would gather information on these guerilla groups, locate, and coordinate effective strikes using conventional forces. Through experience it became evident that recce soldiers operating in small groups needed to be motivated and self reliant. They should also be able to act on their own initiative, motivated and trained in a wide range of military and survival skills.

Most subjects covered at the school were not new to the soldiers on the course. The principals of establishing an OP, its siting, concealment and routine. Tactics and patrolling skills including contact drills. Insertion by helicopter including heli abseiling. Selection of landing zones. River crossings, use of foreign weapons, patrol and personal equipment and navigation was among the many subjects covered and practiced on the course.

The school’s supplied weapon was the 7.62 H&K G3 rifle, sliding stock version. An effective battle rifle which was in service around the world. For exercise/blank firing it had a small, unobtrusive device screwed onto the muzzle which hardly altered weight or appearance to the weapon. One of the best I have seen for the purpose . For field firing we used the BW blue training round. Cartridge and projectile were made of light blue plastic with standard brass base and primer. However these rounds despite being made of plastic could be lethal and not to be treated as blank ammunition. The advantage was that the bullet lost its energy after a few hundred metres enabling live drills to be conducted anywhere on the training area with reasonable caution . A great training aid for its time. The DS evaluated each groups contact drills and corrected any major issues and all were highly experienced, good instructors. Moreover the instruction was never dogmatic and during debriefs discussion and the sharing of information was encouraged.

On the course we practised water crossings, the method of crossing was similar for all. Equipment was waterproofed in our rucksacks, then webbing equipment was attached to the rucksack for the crossing. We took our uniform off placed in a dry bag and wore waterproofs only and boots for the crossing. Equipment bundle being pushed ahead as you swam, weapon at ready on the bundle. The problem was that often this large bundle had to be tightly bound together. In winter trying to undo these wet knots in the cold was a nightmare at night in tactical conditions. We had made locally a river crossing sack. Made out of IPK groundsheet material simply folded in half and stitched along the bottom and one side. It was simply a giant sack which all equipment could be thrown into. It was not waterproof, but more stable in the water and far easier to handle. We had replaced cord with inch wide climbing tape, far lighter and easier to secure the bundle. The Danish Jaeger recce soldiers on the course found this simple inexpensive idea brilliant and were keen to use it themselves as much of their work consisted swimming to islands ,or crossing waterways around their homeland.

As with all the courses after a week of instruction ,demonstration and practice there was a final exercise. The patrol course had the aim of establishing an OP and various situations fed into the exercise to test our drills. Before the start of any mission orders are given. Information in form of air photos and maps were supplied for the mission. Patrols were selected, usually a mix of two nations. Then a Patrol Commander would be designated, he would then set about planning the mission. One patrol was always inserted by helicopter abseil, the others by foot.

Most OPs were on the surface, in dense cover, though whenever possible some form of digging for protection against fire was constructed. This could range from a scrape ( a depression in the ground) to complete overhead cover. One had to balance the pro and cons of digging. Noise is the chief concern and where to place the removed earth is another major factor. Moving into an OP is an art within itself, no sign or trace could be left to attract the curiosity of the enemy. Attention to detail was important. Grass was gently pushed back upright after you had crawled over it. Branches bent back into place or footprints removed, so as to give no indication that something had made its way into that piece of vegetation or building

Once in the OP location a communication check was established. It was always stressed however wonderful or concealed your OP was, if you could not communicate, you might as well not be there. The nightmare for every commander was moving into the location for a well sighted OP and finding he could not communicate from there and would have to move. Now came the essence of long range reconnaissance. Waiting, watching, reporting. This came in the form of observing a target building and monitoring the routine of personnel or the movement of vehicles. In reality this phase could last anything from a day to months but for the purpose of the exercise usually about 48 hours. Once the observation phase was over came the extraction from the OP. Often the scenario was the OP was about to be compromised or attacked, to test contact drills. Then followed movement to an emergency RV, if the patrol had been split up, which was a meeting point where they could rally and decide the next course of action.

Then followed the exfiltration or returning to your own lines. There was always pressure put on the patrol to make as much distance as possible from the OP. The greater the distance achieved in the shortest time the larger the search area became for the enemy. Putting a greater strain on their resources. Once at the pick up point, if one was lucky, you could be extracted by helicopter. But more often than not, vehicles were waiting to bring the students back to the Kaserne for a debrief of the exercise and the course.

LRRPS CQB Course

“…there was five of us on our machine-gun when I saw an English soldier 20 metres to our left. Our oldest soldier was shot in the forehead and dropped without a word. Next I was shot in the chest, I felt blood run down my back and I fell. I knew the war was over for me. He shot three of us before I even had a chance to use my rifle. I would like to meet that English soldier, he was a good shot.”

– Grenadier Emil Kury, 109th Reserve Regiment, German Army Somme, July 1916.

The CQB course was highly sought after at the ILLRPS. It was fun with the advantage that unlike other courses where learning or preparation was required in your free time, apart from one or two night shooting sessions the evenings were free. As with other training once the course address was over and the initial fitness test conducted we went straight into weapons familiarisation. Weapons issued at the school were the the 7.62 G3 rifle, with sliding stock. The 9mm UZI Submachine gun and the 9 mm Browning Hi Power pistol. Unlike today the pistol was rarely handled by the average soldier in the British army at that time, he maybe shot it on average once a year. In the Battery we practiced with the pistol regularly as it was a useful weapon in the close confines of an OP.

The first day on the ranges was used to establish the levels of weapon handling and marksmanship of the various personnel on the course. We started with the single action Browning 9mm pistol with its 13 round magazine. An excellent combat pistol for its time. Its service record went back to pre WW2. Only the Berretta M9, introduced to the US forces in 1985, had an equivalent high-capacity magazine. We shot with both hands on the grip, weapon thrust out towards the target, legs wide in a slight crouch. The body aligning itself instinctively to the threat. Though this technique was not dogmaticly insisted on, if you could hit with another stance then it was acceptable. After a few magazines taking our time, checking that we could more or less shoot straight and we were not a danger to others, we moved on to double taps, the art of firing two quick consecutive shots. For close quarter distance, under 10 metres, this was highly effective. The quicker you could operate the trigger, the closer the rounds landed together and what could be better than hitting your enemy with one 9mm, but by two almost simultaneously.

The same procedure was used for the UZI submachine gun and G3 rifle The UZI was the weapon associated with the Israeli Defence Forces and was an iconic small arm. It had been purchased by the BW and was widely issued. It functioned well on the range, though personally I was not that enamoured with it. Though compact it felt like an oversized pistol in the hand, clumsy with its fat pistol like grip. However my preference, aside the weapon was in service by various armies throughout the world and had more than proved itself in combat.

The H&K G3 was a well engineered rifle and like the AK or FN FAL could be found in various conflict zones around the world. Its pedigree went back to the German Stg43/44. A firearm that defined assault rifle design. It fulfilled the first requirement of a military weapon, reliability, without a problem. It was robust and well engineered,its magazines light but sturdy, devoid of sharp edges, disassembly and assembly was simple. We were issued the Paratrooper version with sliding stock. This helped reduced the overall length of the weapon, however it could be a bit unforgiving on the cheek bones due to recoil of its 7.62 NATO round, but otherwise it was a great rifle.

From engaging targets face on, we progressed to turning drills. This involved some trust at this point as you had another person with a loaded weapon behind you or their muzzle would pass by your body. We knew at what level our own weapon training was, but no idea of the standard amongst other nations, but no doubt they were having the same thoughts about us.

We were now wearing the pistol all the time on the ranges as our secondary weapon. We would engage with our primary weapon, rifle or SMG, reloading as necessary, but if rushed by the enemy or out of ammunition the secondary weapon was drawn, and the enemy engaged. We would let the primary weapon drop to the side on its assault sling, drawing the 9mm Browning and keep fire bearing onto the target. Individual drills mastered, we moved on to patrol drills on the range. This technique is common throughout the Army today but this was not the case in the 1980s.

The range was about 200 metres long with steep embankments either side. As with most ranges it was clean, just grass, devoid of any cover or obstacles. The DS set about introducing us to the area. Logs and oil drums were set up in various configurations so we could practice the use of cover. Communication on the range was important, it was clear and loud. Cries of MAGAZINE! (I’m changing mags) CONTACT FRONT,! (indicating direction of enemy) AMMUNITION! (no ammo remaining) MOVE! (Move now I’m covering) in various languages echoed on the range. The idea being, if possible, to avoid a contact with the enemy, but if a firefight should ensue, the reaction should be fast and aggressive. However this did not mean firing a barrage of unaimed automatic fire. The idea was to keep a steady rate of accurate fire onto the target. Empty magazines were thrown down the front of combat smocks to be later reloaded as or if the opportunity presented. A large amount of 4 /73 personnel wore full webbing including ammo pouches, water bottle pouches and a survival pouch at a minimum. In comparison the Belgium Paras wore just a belt with water bottle & ammo pouch. US forces were similar. Italians had just been issued with Israeli style combat vests,which were quite impressive. They managed to resist some lucrative cash offers to sell the vests from various personnel on the course. The final drill we practised as a patrol was the casualty evacuation drill.

On the night before the casualty evacuation drill it had rained all night, leaving the range at least ankle deep in water.However in the middle of the range was a small piece of raised ground forming a small dry island just large enough to take an average person lying down. The small island became a magnet for the designated casualty. The designated casualty would move out through the flooded range but with uncanny timing always reach the small island to collapse on once the firing started. We did our casualty evacuation slightly differently. Attached to us on the course was a former commando gunner captain. A great guy, but due to his administration position in our battery, not as practised in our drills. He volunteerd to be the casualty, which I thought odd at the time as nobody wants to be dragged across the range and especially as he was a former RSM and always immaculately turned out.

He, like the others paced himself to collapse on the dry piece of land in the centre of the range. Shots downrange from the DS behind us, initiated the contact and we returned fire towards the targets. The patrol commander indicated we had a casualty and I as the Patrol Medic ran foward. As I reached our captain he raised his arm hoping it would be grabbed so it would be easier for me to pull him up onto my shoulders . I knocked his arm away, and grabbed a fistful of webbing shoulder strap and combat smock. There was a split second look of confusion in his face, then I realised he thought we did our drills like the others. I managed a quick “Sorry sir, but…”and then pulled him along the ground with as much strength as I had, which was unluckily covered in six inches of muddy water at the time. I heard splutters and gasps behind me as the water washed over him. I heaved him behind a log, into cover to assess his wounds. The DS leant over me. “Whats your actions now?” he shouted between the gunfire. Asessing his injury, is he dead or does he require aid?” I yelled back. If someone had arterial bleeding, by the time you had dragged him 20 metres he could have bled to death. In such a case immediate medical action was needed. Quickly into cover, check and extract.

Also, the harsh reality was, if it was obvious the casualty had not survived the contact, trying to extract a dead body under fire would only slow down and endanger the rest of the patrol. The other two members of the patrol were now level with me pouring fire into the targets ready to cover or assist in the extraction. One of them was already on my shoulder about to grab the other webbing shoulder strap of our wet, soggy, ‘wounded’ Captain. A thumbs up from the DS and then the exercise was called to a halt. “That’s the advantage of wearing load bearing straps guys, easier to drag the casualty out of fire!” the DS explained, clapping our dripping Captain on the shoulder. Our officer took it with humour and made a comment about ‘breaking the golden rule of all soldiers, never volunteer!’

We moved into an open exercise area in the following days, practising our drills in realistic terrain. One of the more interesting exercises was the so called ‘jungle lane’. Targets were set up, concealed along a route. The task was to patrol down the route in pairs, once targets were seen, they were to be engaged immediately with a few shots of semi-automatic fire, then we were to rapidly move into cover from where we could engage again. A second man behind you gave you covering fire as you moved. The targets were semi camouflaged or had old uniforms draped over them. Good observation was required to locate them.

Before we started on the exercise, we were told to prepare for battle. For British soldiers this meant fully loading all magazines, attaching personal camouflage vegetation, checking equipment and faces camouflaged with cream. My partner for this exercise was our Captain who seemed to bear no grudge for his soaking a few days earlier. He was keen to do the exercise and even suggested we team up for it. The DS came up to us asking, “ready to go guys? “….” one moment “I said, as I slipped the elastic headband of my glasses behind my head. “Oh,for f***s sake! This is going to be fun!” said one of the DSs as soon as he saw my glasses. The other suggested they get flak jackets and helmets for their own safety due to my shortsightedness. The ribbing continued relentlessly all the way up to the start point.

“So, you are the Scout, see the path OK?” said the Hereford DS “then off you go”. After a few metres I spotted the first target, quick double tap, move into cover, few more shots. “OK, let’s see if we hit it Mr Magoo” said the DS. On examining the target, all rounds had struck. “OK, change round you two” the Captain was now lead man I was his cover. He moved up the path, scanning for targets. It’s then I saw to the left of the path the edge of a target placed behind a tree. It was just the edge exposed, maybe a few inches. Our captain missed it completely, he was intensely looking into the scrub to his right. I looked at the DS, they had seen that the obvious target had not been detected but indicated to me to wait. The target was a prime example of when you concentrate on the hidden you can miss the obvious, a mistake that other teams also made on the lane. Our captain was now level with the target, about 20 metres in front of me, less than an arms length to his left. I looked at the DS and they nodded. My reaction then was the nightmare of every range supervisor .

On receiving the nod, I swung my weapon up, aimed and fired. I fired half a dozen rounds in rapid succession. Bark flew off the tree, rounds hit the target and wood splinters showered our captain. I lowerd my rifle and looked at the DS, but saw death looks coming from both of them. It seems, a misunderstanding had taken place. One of the DS let out a deep breath, then asked calmly ” Why did you shoot, and not shout a warning?” I answered, “He was level with the threat or rather it was behind him, I thought he couldn’t engage the target in time” I replied. Both DSs looked at each other, “Fair enough” they mused, “would have done the same. It’s good to have confidence in your own ability, but common-sense safety, that was close. OK?”. The point was taken in, the line between realistic training and safety could be a thin one. It was easy to become so concentrated on the task that safety factors were blocked out and this is when accidents took place. Our Captain joined us, shaking tree bark out of his smock. “He really doesn’t like you, does he sir?! ” said the DS to our captain with a grin. He took this with humour again, to his credit, but did suggest we complete the rest of exercise with me as lead man.

Most other nations rushed foward and threw the casualty directly onto their shoulders, turned and ran. This required the rescuer to be strong and remain standing as he heaved the wounded from the ground. A criticism from the DS was both parties were exposing themselves to fire, especially the wounded on his back This was seen pragmatically by the Belgians.” I save him, he saves me!” said one of the Belgian Paras with a shrug.

Unarmed Combat was also taught on the course. One would encounter arrest techniques as part of Northern Ireland training but rarely was it practiced on a regular basis. The Army promoted boxing and judo; both are excellent for self defence but were mainly kept as a sport. They were sadly never taught together as tools in unarmed combat. We ran to the vehicle garages in the Kaserne and either practiced there or on the grass outside. Padded judo mats were used in the garage for throws. Strike pads were used to practice blows with hands and feet. The combat was a mix of judo, boxing and JuJitsu. Blows, kicks, takedowns as well as throws were taught. The idea being, to strike, incapacitate and go. There were a few practised martial artists on the course, but there was a big difference between the sporting environment of the training hall in appropriate clothing and footwear to the unforgiving concrete or ground whilst wearing boots and equipment . Also we had no safety equipment, padded gloves, headguards, shin pads etc. Each individual had to show both restraint and enthusiasm in training. Despite the high motivation of the participants grappling, sparring, throwing, stabbing with wooden knives, no one received more than a few bruises or a fat lip.

Not everyday was spent on the ranges. We were invited to visit Heckler & Koch, the German weapons manufacturer. The firm was known throughout the world as building tough reliable small arms. They also had a very successful marketing department which contributed greatly to their success. We were first driven to a restaurant lodge, which specialised in wild game on the menu and we were treated to a first class meal. After the meal we boarded the bus to be taken to H&Ks test range. I was expecting to be taken to some modern industrial complex, but instead we arrived at a large farm house in the country side. Surrounded by fields, it looked more like a weekend getaway than a test range. Inside it was very evident that this was not a hotel. A few HK posters lined the plain walls in the reception area, then we were led into the armoury.

The armoury was a small room but lined with HK weapons all around the walls. In one corner was a test bench for rifle accuracy with a PSG 1 sniper rifle set up. It pointed out onto a 100 metre range. There was a TV screen by the shooters seat which was focused on the rifles target. The target could be inspected on screen and changed by a cable system. The PSG1 was one of very few purpose-built semi-automatic sniper rifles available at the time. It was a heavy beast in comparison to most sniper rifles in service. Probably too heavy and ungainly for the military sniper I thought. But however a hot favorite for police type units. GSG 9 had it in service and various police SEKs (Sonder Einsatz Kommando/SWAT) in Germany. Its function & accuracy was demonstrated by the range assistant. At 100 metres, a 3 round clover leaf in the bull was achieved by the range assistent Then we were invited to take part in a small competition. 3 rounds, whoever hit the middle of the zero in the 10 on the target won. We all tried our luck, the scope settings were left as they were, so intelligent guess work was needed to judge shot placement. Eventually we had a winner, beating the majority of infantry shots, a 4 /73 man as well.

On the range we had the entire H&K range demonstrated, from handgun to light machine guns. Of the many types that were presented to us, the HK MP5 and it variants impressed me the most. From the MP5K (Kurz/short) carried on a shoulder holster to the SD (Schalldämpfer /suppressor) version. The weapon had the advantage that it fired from a closed bolt, so it was very silent, and accurate. The bolt moving back and forwards seemed to make more noise than the discharge from the weapon. The representative from H&K was so confident with its lack of noise he fired it into the front lawn of the range. ‘This never disturbs the neighbours!” he said. One of the more unusual versions of the MP5 was the executive briefcase configuration. The MP5 within the case could be fired by means of a trigger switch in the cases grip. The case was a favourite amongst Close Protection teams. Firing it was an experience, a definite James Bond feeling for about a second, which is all it took to empty the shortened 15 round magazine attached to the weapon. All weapons worked with the same rolling bolt system, so internally SMG, rifle and LMG were the same weapon. The trained on one, trained on all principle. We left the range with a ton of promotional material and a great insight into weapon’s development. I later was told the HK visits were discontinued shortly after our course. It was rare that soldiers or NCOs were treated to corporate entertainment, so we were lucky to have had this experience.

Night firing was conducted under various light conditions. As the light disappeared we practiced individual drills on barely visible targets. Once the light was fully gone we used aids such as illumination by flare and torch. Firing wearing PNGs (passive night vision goggles) was also practiced.

As British soldiers we were naturally proud of our army and our regiment and unit. Our ongoing operations in Northern Ireland and our hard-fought success in the Falkland Islands made us feel quite experienced compared to other Armies. Often, we could develop a superior attitude and forget the problems other Armies had. Whilst discussing contact drills our DS asked if anyone had experienced a fire fight. Before our involvement in Iraq, Afghanistan etc. the opportunity to be involved in a live contact was rare. “Anyone been involved in one, anyone, anyone… ??” asked our DS. We all looked blankly at each other then a hand shot up at the back. We all turned, the hand’s owner was a rather short Italian soldier. “You?! Well… How did that happen?” asked the suprised DS . “Si Sergente, supporting the Carabinieri in its operations against the Mafia, many times we were shot at… I can remember at least, five, six times from AKs, automatic weapons, “said our Italian colleague. He then went on to share his experiences with us. Of all the people there, this small unassuming Italian soldier had fired the most shots in action! It totally crushed outdated clichés about the Italian military and was an example of ‘never underestimate anyone’.

Our range tasks increased in their complexity. We were now doing short patrols and a contact was initiated at some point en route. We were given a brief by the DS that the enemy had set up a well defended OP on a high feature and it was being used to direct Artillery fire. We were to advance to the position and neutralize it. Approach silently but once in contact with the enemy, fight through to the OP and destroy it. On the information given, we issued brief orders for the task ahead. We patrolled in as a 4 man team and moved foward. At one point a camouflaged target popped up, which was engaged. Surprise was gone, now it was all about speed and firepower. We worked in two groups of two firing, covering each other. Targets popped up as we bound foward. The stamina required for this type of activity cannot be underestimated.

You are sprinting maybe 10-20 metres, then throwing yourself to the ground. Your equipment weighs you down, spare magazines tucked down your smock dig into your body. You are shouting at the top of your lungs, while running, and trying to track your partner, keeping close but not running into his line of fire. The noise is immense. You are also jumping over fallen logs, obstacles, but still looking out for cover. The heart is racing, lungs heaving but you are still trying to accurately fire and be effective with the limited ammunition you have.

The enemy camp, was realistically constructed, it had shelters, a fire in the middle, cooking equipment, chairs a few jerry cans etc. Targets were hidden in shelters, behind cover and were duly engaged. We could see the OP, a few hundred metres away, a sandbagged bunker, again constructed by the DS. One team peeled to the side to allow the other to assault the OP whilst they gave a steady stream of covering fire. The assault team would now cover each other as they moved foward. Eventually as part of the assault team I was nearest to the bunker and rushed foward and sticking my muzzle into the vision slit fired a burst into the bunker. The inside disappeared in a cloud of dust. By then my partner was at the entrance doing the same, more dust bellowed out of the vision ports, and I could hear the wack of rounds striking the sandbags. We secured the position, and our cover team joined us. The DS de-briefed us on site, the only critique was that the cover teams margin of error was slim. Bullets were still striking the sandbagged bunker as we rushed foward the last few metres. “Beware of tunnel vision guys,” our DS said “One eye on your guys, the other on the enemy and keep well back from entry points and observation slits, if your fire crosses, you’ll hit each other! Otherwise good communication, good movement! “

The effort the DS had put in to create realistic scenarios always impressed me and ultimately provided us with a first class training experience.

LRRPS Medics Course

“The knives appear somewhat blunt”

– Lord Uxbridge speaking to his surgeon whilst having his leg amputated after it was hit by a cannon shot at Waterloo in 1815.

In the case where a soldier is wounded, he will most likely be initially treated by his own comrades. The next step would be removal from battlefield. Either by his own unit or medical specialists, and now his recovery journey would begin. Moving further back and receiving hopefully increased care. A soldier behind the lines did not have this chain of support and would have to rely on his patrol for medical aid or if it could be trusted, local aid. The chances of being lifted out by helicopter would also be slim if you did not have total air superiority.

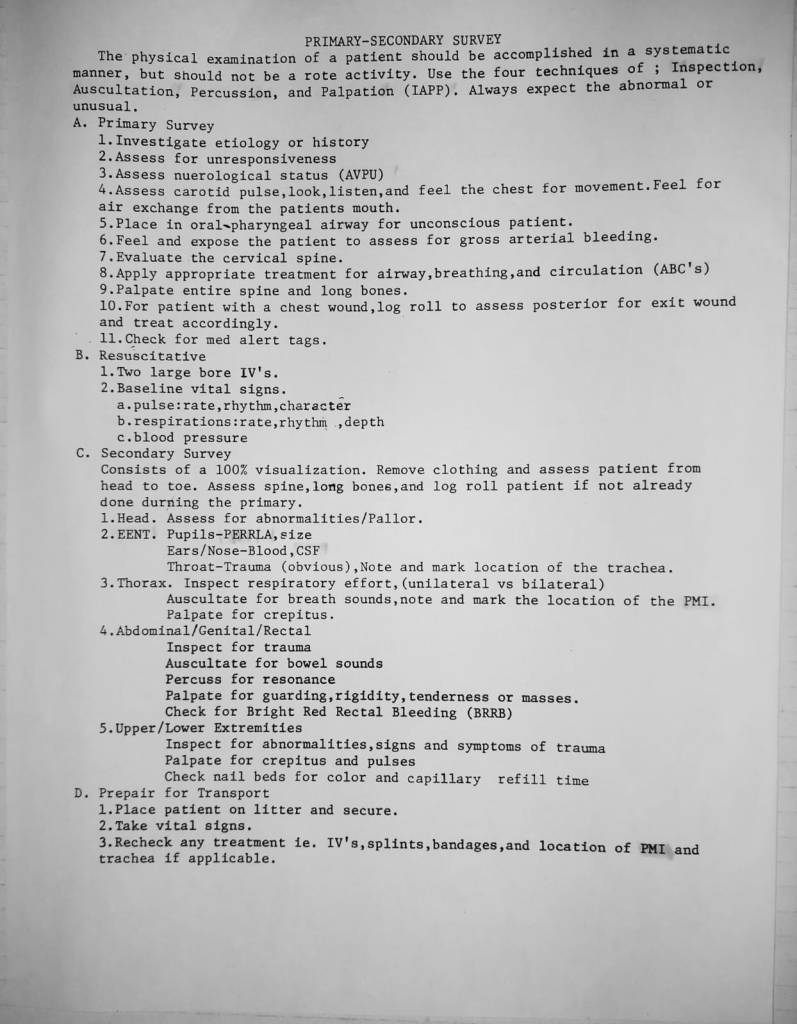

This course started with a PT test, the same as many others. We were introduced to our instructors, Chief of course was a BW medical officer. Then a Chief Instructor in all matters medical, from Hereford UK, and finally two US Green Berets. Who were stationed in Bad Tölz, Bavaria. On entering the class every table had a collection of syringes, needles, sterile water bottles and hygiene articles at hand. We were thrown straight in at the deep end. The ability to find a vein to introduce life saving fluids to a casualty was paramount. It can sometimes be a challenge even in peace time medical practice. We may have to do this in a combat setting, so practice makes perfect. Within half an hour we were injecting ourselves, or each other, on various points of the body with sterile water. This got us used to the hygiene procedures required and built up our confidence in handling syringes and needles. Within a few days we had moved on to intravenous injections, catheters, administering IV fluids and this became routine every morning.

As others did physical training every morning, for us, it was locating a vein, catheter, the giving of fluids or extracting blood. Just as we became comfortable with the ‘standard’ needle, the DS started giving us bigger diameter needles. I cannot remember the exact medical specification of the sizes but the last needle was an impressive size. The larger diameter of the needle, the quicker fluids could enter the body. Having it inserted was not a pleasant experience.

The course covered a wide variety of battlefield injurys and their treatment, establishing an airway, medication and drugs, wound management, anatomy, suturing, long term care, psychological issues and survival medicine, all this was packed into 10 days of instructions. The Green Berets were brilliant teachers and were passionate about their subject. US Special Forces medics went through one of the most thorough and intense military medical courses in the world. The patrol Medic was a job that required a lot of dedication. There was a written test virtually every two days, ensuring you were doing homework in the evenings and taking in the information. But despite the intensity and pace we were also given two highly informative lectures. Both speakers were surgeons but held positions in the German Army Medical Reserve Forces.

Our first speaker was a recreational big game hunter. He showed us, some of the various injuries he had come across on several Safaris and how he had dealt with them, often using local materials or minor surgery using a Swiss Army Knife. It was a classic example of bush doctor skills and highly informative, teaching us never to be scared to improvise.

The second speaker left a lasting impression on me. He had operated in Afghanistan as a doctor and surgeon aiding the Mujahideen during the time of the Soviet invasion. He operated with just an interpreter and a minimum of medical supplies. The resilience of the Afghan fighters was impressive. We were shown an old man, that must have been in his 70s that had been injured while removing explosives from an unexploded shell to make a booby trap. His face and eyes had been injured. Despite the distance to the doctor the old man had trekked two weeks to find him. On his arrival the old man’s wounds were infested with maggots. Though this had actually helped to stop the spread of infection. Many think maggots eat only infected flesh. Not totally accurate, they tend to eat this first but will eventually eat healthy flesh. The doctor had to remove the eye, and patched the old man up. Once the operation was finished and wound dressed the old man asked if he could go as he had work to do. Despite the offer of rest for a few days he returned to his village, to continue with his job of making booby traps.

Another story of an incident gave us further insight into the mindset of the fighters. A group of Mujahideen brought a casualty in. He was dead, badly burnt, no human could have had survived the injuries. The body was seen to move nothing more than muscle contractions due to the nature of his death. The doctors explained why he was moving but the fighters did not accept it. He moves so he is alive. Operate, if you refuse we kill you. Others argued that the doctor had risked his life to come and help them and should not be threatened. To the fighters this was irrelevant, the casualty came from their group and it was up to them to do their best for him. The doctor wisely set up an operation and told them, untruthfully, yes, he had survived and they were right about him. He must be an exceptional warrior. After a while he said that the man had died on the table but was very tough to even live that long. This satisfied the group who thanked him for his efforts. If he needed help in the future they would come, wished him well, and left.

The tenacity of the fighters, their loyalty to their group, and their patience and determination was impressive. Any unwanted outsider was an enemy, a threat. It did not matter what you came with, if not wanted, leave or face the consequences. Years later after 9/11 when we announced, as part of a coalition, to go back into Afghanistan the images of this lecture came back to me. My thought then was : Are we really aware of what we are facing?

As a final exam we had several test papers to complete and a practical test to pass. The practical test was nerve wracking. Each student was brought into a room, on the floor was a casualty. Each casualty had two judges. Mine was the German medical officer and the instructor from Hereford. On the ground was a live casualty. A German soldier from the barracks. Tubes had been taped along his arms, and legs to simulate veins. Since the soldier would have to be the casualty for at least a dozen students this saved him from a lot of potential discomfort. Computer training aids are common nowadays, and without a doubt invaluable to medical training. Since we did not have these, the student had to constantly explain what he was doing and the DS examiners fed him information as he dealt with the casualty.

Mine had an obvious injury, a gunshot or fragmentation wound. Naturally he was deemed as unconscious, so no feedback on history of events before you reached the casualty. I started what was then called a primary survey. Most of the terms came from American first aid procedures. ABC, Airway, Breathing, Circulation. Airway clear, then start at the head, feel, look, check. C7, the top 7 vertebrae to the skull, any abnormalities, does his neck have to be secured? If so, secure the head, scan down the body etc. This check was fairly rapid, the more obvious wound was detected and dealt with. An air way secured, and an IV established. Normally now the secondary survey would take place. This was detailed survey top to toe. It was at this point you would discover another problem. Normally the result of an internal injury, hidden from view. Information was fed to you rapidly. Pulse increasing. BP dropping. Twitching, Casualty gasping etc. Your mind would race to find the problem. If you diagnosed the symptoms correctly and reacted correctly the casualtys condition would improve. Once the casualty was more or less stabilised, more questions would follow concerning long-term treatment, or on drugs and dosages. After about what seemed a lifetime, but in reality, was about 15 minutes, the examiners would stop the exercise. But would not inform you until the end if you had passed.

Before the course ended we received a debrief on our test. We were encouraged to learn further and get as much experience as possible. We had in fact established contact with the SF medics to work in their medical centre at Bad Tölz. As chief sponsor of the medics course the US generously gave fully equipped medical bags to every student on the course. The same type as used by their own forces. They were fully stocked with instruments, scalpels, stethoscope, suture kits, airways, bandages, drugs and surprisingly even morphine! We were not asked to sign anything for the contents,but never once did controlled drugs not reach our medical stores.

LRRP Leaders Course

“He then gave us a vast area of mountainous jungle, on the east side of Kohima and Imphal, measuring 80 by 50 miles which we were to patrol on foot with animal transport only. Our orders were to keep the area clear of Japanese patrols and infiltrators… and since we were expected to live of the land, we took shotguns and fishing rods… “

– -Captain Dick Richards 50th Indian Parachute Brigade Burma 1944.

This was a pilot course when I attended and the main theme was preparation and planning necessary for a LRRP patrol. Close target recce, appreciation of ground, seasonal problems, rehearsals and communications were discussed. Though similar in many ways to the patrol course the emphasis was on the NCO finding solutions to problems. There was a lot of discussion between the nations. It became very clear that some nations had totally different concepts of long range patrolling. Other nations used their recce for a whole range of tasks, ambushing, raids, casualty extraction. We specialised in OPs of all types to achieve fire control for the Artillery. Britain, with many post war conflicts, had used LRRP patrols in its counter insurgency operations. Covert OPs were being used routinely at the time in Northern Ireland to fight against terrorism so these skills were current and constantly being updated.

I found that most other units knew only one type of OP, above surface, concealed in vegetation. In the battery we had tried many different types of OP. Above surface, sub surface dug, urban, and use of the MEXE shelter. We were well practiced in OP routine, and could pass on this knowledge on the course to other units attending.

One of the vital ingredients to a successful patrol is good set of orders. Orders are clear concise instruction as to how the mission is to be carried out. They also act as a check list for the commander that every eventuality is planned for.

We were divided up into 4 man patrols. I was given the job as commander of the patrol. I had another 4/73 member and two German paratroopers from the Fernspähkompanie (recce company) as well. One spoke good English, the other only a fraction, and relied on his mate to translate. However both were very keen and very helpful. For the end exercise we were tasked with a CTR (Close Target Recce) and observation of a particular building. Aerial photographs and maps were provided, and we were assigned a space in the large attic where we could plan our mission and build a model. The two German paratroopers enthusiastically volunteered to make the model. I was a bit unsure whether to give them this task. One has the tendency to become a control freak when you are not quite sure of the type of people you are working with. However, if all the organisation was just taken over by myself and the other Brit, this would not encourage team work and trust. I said yes, hoping I had made the right decision. My worries were unnecessary, two days later, the model was revealed and it was as detailed and professional as I have ever seen. When it came to issuing orders, I could summarise each phrase in my limited German for the less fluent in English. Though the standard school language was English, this made me appreciate the difficulties that non English speakers faced on courses.

We had enough time to prepare, rehearse our drills. These were designed so whatever the situation, everyone knew what to do in this event. We practised action on contact, moving in and out the OP. What could not be practised was discussed so every one was working to the same format.

All went well on the exercise, we reached our OP, situated in dense forest. Communications was good so the first fears were waylaid. We set up two watches, one German, one Brit in each group. We monitored vehicle movements on the road before us. Various vehicles would drive by with boards on the side. On the boards were large photos of Warsaw Pact equipment. These were duly reported back to our exercise HQ and recorded. After a few days the OP was eventually compromised by an enemy sweep and we had to evacuate the OP and make our way to our pick up point. We forced our pace through the night and the march to the pick up point had been arduous. We still needed to take short breaks. Every half an hour we would stop for 5 minutes, hydrate, check and confer on our location. Not everyone was map reading so the breaks kept the patrol up to date with progress and informed each member where we were.

We finally reached our pick up in the early hours. I checked the map several times, and conferred with the others. We wanted to be totally sure we were at the right point. It was a large horshoe clearing surrounded by thick woods. The open end of the horseshoe clearing dropped away into a steep valley beyond. We moved into the area at the woods edge and waited, concealed. We were sceptical that a helicopter would materialise. Plan B was a long march back to the Kaserne.

Then faintly in the distance we heard a soft clak clak clak, we waited, but nothing. It was a few minutes past pick up and someone suggested the noise we had heard was a train in the distance. A few birds chirped, nature’s signal that it would soon be light. Then suddenly there was a roar of aviation motors, and from the valley beyond the clearing the black silhouette of a RAF Chinook helicopter appeared. It had hid its approach by flying at tree top level through the valleys. It hovered a few metres above the clearing, nose towards us, then swung 180° on its axis in the air and came to rest with its ramp down in our direction. The load master flashed a redlight and from various points of the clearing, patrols broke cover and ran towards the Chinook.

We were unaware where each patrol had been, but all had found their individual 8 figure grid reference around the clearing. Within a minute, we were all seated, Bergens before our feet, strapping in. The load master checked the area quickly and the ramp was raised, and we lifted off. Our stomachs rose as the Chinook dropped into the valley and we were shaken back and forth as it followed its tactical route along the floor of the feature. After a few minutes it climbed and leveled out and we relaxed. All faces were dirty with camouflage cream, some stretched out, glad not to have the weight of their bergens on their backs. Any chocolate found in the depths of combat smocks was shared around. Despite the noise of the engines some dozed, others talked and joked. The sun was just coming up and once fully in flight the ramp was lowered in the air and the sunrise flooded the inside of the interior. We were treated to an amazing panorama, flying above a frosty countryside of Southern Germany with the Alps far in the distant horizon. A unique perspective from a Chinook helicopter and a great end to my final course as it was to be at ILLRPS.

Summary

That concludes, my memories of the LRRPS Weingarten. What I enjoyed most was working with other nations, and knowing we had a common goal. Both blogs are intended to give an idea as to what it was like to serve as a soldier in the 1980s, during the Cold War. For many this period was regarded as very surreal, or a huge game almost. But for us (4/73) we trained with the worst case scenario in mind. Also to show the work of ILRRPS, from the student’s perspective and many thanks to our instructors for their efforts and knowledge

“Mankind has had ten thousand years of experience at fighting and if we must fight, we have no excuse for not fighting well“.

Col. T. E Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) 1918.

Author Bio

Kim Read enlisted in the British Army 1974 at the age of 16 joining the Junior Leaders Regiment RA based at Bramcote, UK. On the completion of training he joined 32 Light Regiment RA in Bulford UK and trained on the 105mm Pack Howitzer. Later the Regiment’s role changed to guided weapons where he trained on the Blowpipe anti aircraft missile and later became a Swingfire anti tank crew commander. He volunteered for Special OP Troop selection joining the unit in 1986 until he left the Army in 1992. During his service Kim completed tours in Northern Ireland, Belize, Cyprus, Germany, Gulf, Canada, Turkey and points between.

Abbreviations

DS…………. Directing Staff/Instructor’s .

PUP…………Pick up Point

OP…………..Observation Post

‘Bergan’…..General name for military rucksack (British)

BW………….Bundeswehr/German Armed Forces

NCO………..Non-commissioned officers,

MEXE……..Military Engineering Experimental Establishment

Recce……..short for reconnaissance

IV…………….Intravenous

IPK………….Individual Protection Kit

H&K…………Heckler & Koch

Mp…………..Maschinepistole (sub machine gun)

Kaserne…..Military barracks, German

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved by the Unconventional Soldier blog. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing of the author.

Very interesting read. I love small stuff of innovation especially where you mention the ipp sack for water crossings. Are any of the course notes available on the internet?

LikeLike

Thanks for reading Ryan. Unfortunately no notes that I am aware of. Rather unfortunate that I got rid of mine many years ago when having a clear out.

LikeLike