By Nick Lipscombe FRHistS

Royal Artillery Stay Behind Observation Parties

“But Bagnall set about persuading the West German Government that some ground would have to be surrendered in order to withstand a massive Soviet Army attack, and it was into this area that small parties of well-trained soldiers, in the guise of SBPs and SBOPs would deploy and operate.”

It is an important question to ask and/or clarify as to why the regular artillery were required to stand up stay behind observations parties (SBOPs) to supplement other special forces undertaking this task as Stay Behind Patrols (SBPs) during the Cold War. General Nigel Bagnall had long since felt (when he was GOC 4th Armoured Division in the mid-1970s) that the static linear defence of the NATO General Deployment Plan (GDP) was far too reactive. When he became Commander 1st British Corps in 1980 and Commander Northern Army Group (NORTHAG) in 1983, he set about changing this.

The battle against Group of Soviet Forces Germany (GSFG) would now be one of mobile defence and defence in depth. It is understandable that West Germany continuously tried to pose restrictions on the concept of ‘mobile defence’ by insisting that the GSFG be engaged as close to the Inner German Border (IGB) as possible. But Bagnall set about persuading the West German Government that some ground would have to be surrendered in order to withstand a massive Soviet Army attack, and it was into this area that small parties of well-trained soldiers, in the guise of SBPs and SBOPs would deploy and operate. The Stay Behind concept, which had already been part of the more static NATO deployment plan, now evolved and expanded at a fast pace.

The key question was why couldn’t the existing special forces (SF) or formation recce undertake the role of acquiring targets for the long-range artillery? (Note: This was the question Kev and Colin asked Tony Stone in Podcast 2. The answer was not quite complete and this may have been because General Stone did not want to be seen as in any way critical to the TA SAS and/or HAC as an STA/SBOP capability.) The regular 22 Special Air Service (SAS) were completely committed to other tasks, the Corps Patrol Unit (CPU) from 21 and 23 SAS had an intelligence gathering role as well as target acquisition role and this drove their deployed locations and modus operandi.

The Honourable Artillery Company (HAC), were the only dedicated Surveillance and Target Acquisition (STA) capability employed in the stay behind method. During the 1970s a series of exercises had taken place, known as BADGER’S LAIR, designed to determine the viability of both the CPU and HAC, designated Stay Behind Parties (SBPs) in their roles. The HAC had, in point of fact, begun their new role in late 1973 and in early 1977 the first Sabre Selection Course (SSC) was run.

Successful candidates were presented a black lanyard to denote the rather special nature of their new task within the Regiment. SSC 2 and 3 followed in late 77 and early 78 and then, hot on the heels of SSC 3, the three newly formed sabres undertook a two-week exercise at the International Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol School (ILRRPS) in Bavaria, West Germany. This went well and, as far as I can recall, one sabre squadron was allocated to each of the three UK divisions based in Germany. The problem, therefore, to long range target acquisition looked resolved.

TEMPLE PRIEST Evaluation Exercises

“…during this exercise a hunter force, was provided by the regular and territorial units of the Parachute Regiment, and they were able to locate almost every deployed (old and new concept) hides/OPS from the CPU and HAC.”

Nothing, however, stands still and the sea change to 1 (BR) Corps concept of Operations, as a result of General Bagnall’s vision, better intelligence of the threat (i.e., 3rd Shock Army who were facing the British Corps), improved deployment techniques and equipment and better detection capabilities available to the Soviets, led to a new set of evaluation exercises known as TEMPLE PRIEST. There were three of these, and the first two were mainly concerned with the detectability and ipso facto the survivability of the SBPs. During TEMPLE PRIEST I, run in October 1981, patrols from the CPU and HAC; the former were deployed in what were termed the old and the new concept, while the latter deployed in only the old concept.

The old concept was to deploy a single hide and observe from this, while the new concept was to deploy a hide from which separate OPs were sent and who reported back to the hide. It is important to note, therefore, that this concept of a hide and satellite OPs was not first introduced by the Regular SBOPs, but it was honed. The detection rates of hides and Ops in TEMPLE PRIEST I were over 80% for the CPU and 50% for the HAC giving an average of 72% detection. (Note: The reasons for detection are still too sensitive to list here). There were a series of recommendations following the (slightly disappointing) results from TEMPLE PRIEST I, but none of these suggest that a regular unit or sub unit should be stood up for the role. Although it is clear that staffing for such a unit/sub unit was already well advanced.

There was, not surprisingly, a recommendation for another exercise (TEMPLE PRIEST II), which was conducted in October 1982. This report is not in the public domain. Given the timespan of staffing and standing up of the regular SBOPs in 5 Regiment RA, there would not have been any patrols from this regiment on TEMPLE PRIEST II. If my memory serves me correctly, during this exercise a hunter force, was provided by the regular and territorial units of the Parachute Regiment, and they were able to locate almost every deployed (old and new concept) hides/OPS from the CPU and HAC.

This caused some understandable concern and it was felt using TA units to furnish SBPs close to the IGB, in the covering force area (i.e., in front of the 1st and 4th divisions) in line with the revised GDP, was a tall order. It was clear that a territorial unit would simply not have the requisite time to train, or time to deploy out to area close to the IGB, in order to provide SBOPs fit for purpose. (Note: The options of training the HAC in the parachute role, to overcome this, were also considered). By that I do not mean ‘be any good’ I mean ‘be able to get out and in in time and not be seen’. It was interesting how many German civilians (the proverbial and possible reds under the bed) spotted the HAC and CPU patrols deploying.

There is another element here too that is worth examining, which also explains the HAC’s concerns at the SBOP role in the early 1980s – dovetailing with the findings of TEMPLE PRIEST. I have cut and paste the following from an HAC officer reflecting on the HAC’s early SBOP operational development history. ‘… The Americans first came and gave us a preview in 1980 on TRADOC’s (United States Army Training and Doctrine Command) thoughts on “extending the battlefield”, which involved “deep attack”.

As explained to us, TRADOC/Gen Starry was of the view that with finite forces at its disposal, the US Army (and by extension NATO) would be ill-advised to allow all of them to be chewed up defending against some Soviet-devised attack plan, but rather a major proportion should be committed to an immediate counter-offensive of our own choosing in Warsaw Pact territory – so that the Alliance might have something to trade off against NATO territory lost in a pre-emptive Soviet attack. This notion was subsequently subsumed within the US Army’s 1983 Air Land Battle doctrine, which no doubt compelled NATO into drawing-up its own Follow-On Force Attack (FOFA) doctrine. From then on, training to sit around waiting for the Russians to come to us ceased to seem so enduring a requirement.’ Food for thought.

That aside, the standing up and training of the regular SBOPs of 5 Regiment to encompass the GDP Covering Force area was, as a result of the TEMPLE PRIEST findings and recommendations, given a renewed impetus and momentum. This coincided with Major General Tony Stone’s paper and concept for the establishment of a regular unit from the Royal Artillery to undertake this task. That paper and concept he presented to General Bagnall when he was Commander 1st British Corps. As Tony Stone mentions in his podcast, ‘that in order to create this function, the Royal Artillery (RA) had to start from scratch’. (Note: This is correct in terms of establishment but not so for modus operandi which was already evolving with the HAC). This was the causa viventium of the regular RA Stay Behind Observation Parties (SBOP). (Note: They became Special OPs in 1984 in order to provide some OPSEC to their name/role). As General Stone was, at that time, commanding 5 Heavy Regiment RA, the specialist organisation evolved, first and foremost, in that regular RA unit.

Modus Operandi – The Military Engineering Experimental Establishment (MEXE) Shelter

“Six-man patrols gave the RA SBOPs more flexibility and enabled the patrol to deploy two satellite OPs to the edge of the wood from the mother hide…”

There was a suggestion, in one podcast, that the use of a MEXE shelter was unique to 5th Regiments early deployment and operating trails. This is not quite true. The HAC and CPU were using MEXE shelters as part of their modus operandi and this was one of the main reasons their OPs were so easily compromised. They simply did not have the time to deploy, dig in and camouflage the patrol base and this resulted in many bases being constructed on the edge of, rather than in the centre of, wooded areas (i.e., the old concept). However, it should also be noted that the HAC and CPU were also experimenting with placing MEXE shelters deep inside wooded areas (i.e., the new concept); a deployment option that was later adopted and developed by the Regular RA SBOPs.

This was also the principal reason that the regular observation parties were six-man and not four-man, as they were in the HAC and, indeed, in other specialist/special forces organisations. (Note: One or two additional personnel could be attached to an HAC patrol or OP party but their task was more one of removing vehicles and equipment and camouflaging the OP site once the digging was complete. Also it should be noted that the CPU had practised using 6-man patrols for the new concept in the 1970s and 1980s). Six-man patrols gave the RA SBOPs more flexibility and enabled the patrol to deploy two satellite OPs to the edge of the wood from the mother hide, thereby simultaneously covering two observation areas, or areas of high interest. This was not without additional challenges, as was covered excellently in Sammy Nicholl’s podcast.

Another aspect, and an important one, that I have not heard mentioned on/during the podcasts, is that the initial RA plan was that officers were to lead these six-man patrols. The officer was to be a lieutenant or young captain. I am not clear when this decision was made, I think it was after the first selection course in 1982. I am slightly clearer as to when it was shelved. I received my posting order in autumn 1984 (just prior to Exercise LIONHEART); I wanted 29 Commando but instead my posting order listed me as joining 5 Heavy Regiment as a patrol commander in the SBOPs.

I joined 5 Regiment in January 1985 only to discover that the decision had been changed (probably at the end of 1984) and that two other lieutenants had already been posted out. I was told by the CO of 5th Regiment that I would stay, complete selection (Course 4, I think) and then take over as Troop Commander of the 5th Regiment Troop from Captain Don Grant. I remained in that post until the end of 1987 when Captain David Jones took over. I would add, by way of a conclusion, that it was absolutely the right decision to make a Sergeant or Bombardier the patrol commander.

Recruiting And Manning

“…the SBOP soldier’s role necessitated a level of cerebral capacity that exceed the fundamental requirements of commando and parachute trained soldiers in other units.”

This was a huge challenge in the early days and I note from other later podcasts, with no surprise, that it remains a challenge to this day. Iain Strachan’s excellent podcast outlined the problems on the first selection course and David Jones confirmed that little had changed some 6 years later. Chris Lincoln Jones, however, hit the nail on the head when he compared a soldier from 29 Commando RA, 7 Parachute Regiment RHA and a soldier in the RA SBOPs. They all needed to be fit, that was sine qua non, but the SBOP soldier’s role necessitated a level of cerebral capacity that exceed the fundamental requirements of commando and parachute trained soldiers in other units. And that, in turn, made recruiting such men all the more challenging.

Add to this another problem, one which Tony Stone mentioned more than once, the RA themselves. There were many in the RA who saw no need for more specialist soldiers – 29 and 7 were enough and already represented a drain on the brightest and best in the regular gun, air defence and surveillance regiments within the Royal Regiment. Furthermore, the early/initial recruiters and trainers within the Troop were too discriminating in the early selection courses. As Iain Strachan recalled, there were about 60 or 70 potential recruits on the first selection course and only 15, or so, passed. Yet many of those who failed were suitable material, they just needed to held in some form of ‘potential pool’ and given a second chance. This was later addressed.

One of decisions that was made during my tenure was to convince a sceptical HQ Director Royal Artillery (DRA) to widen the pool of potential recruits to other regiments and corps within the British Army. I noted, with no surprise, that in the fullness of time, David Jones was able to widen the pool to a lake by opening up recruitment from/to the other two Services. This has clearly been a success.

David Jones also talked about undertaking a recruiting drive roadshow across the RA regiments in the late 1980s. I was slightly tickled to hear that he did this with, amongst others, the then CO of 5 Regiment as part of the delivery/recruiting team. When the Director RA tasked 5 Regiment (on behalf of 5 and 32) to do this in 1985, the roadshow consisted on myself and CSgt Geordie Watson. One regiment, that will remain nameless, but which has to this day the lowest regimental number in the RA ORBAT, steadfastly refused to allow the recruiting team through the camp gates.

Finally, the CO of that regiment was ordered by the Master Gunner to permit the team to deliver a talk and canvas potential recruits. Geordie and I set up the presentation (which was a boring Powerpoint only – all we were allowed) and waited some considerable time before the RSM marched the entire regiment, tick-tock fashion, into the gym. We then waited another long period, about 20 minutes I recall, for the CO to arrive. We delivered the talk and then asked if there were any questions. At which point the CO stood up, asked if we had finished, made some reference to his regiment being the best and added a rhetorical question about why would anyone want to join our rag, tag and bob tail unit. Without waiting for an answer, he then ordered the RSM to march the regiment out. That was that. The CO went on to great things but Tony Stone’s point about the RA being one the SBOPs greatest enemies was demonstrated wonderfully.

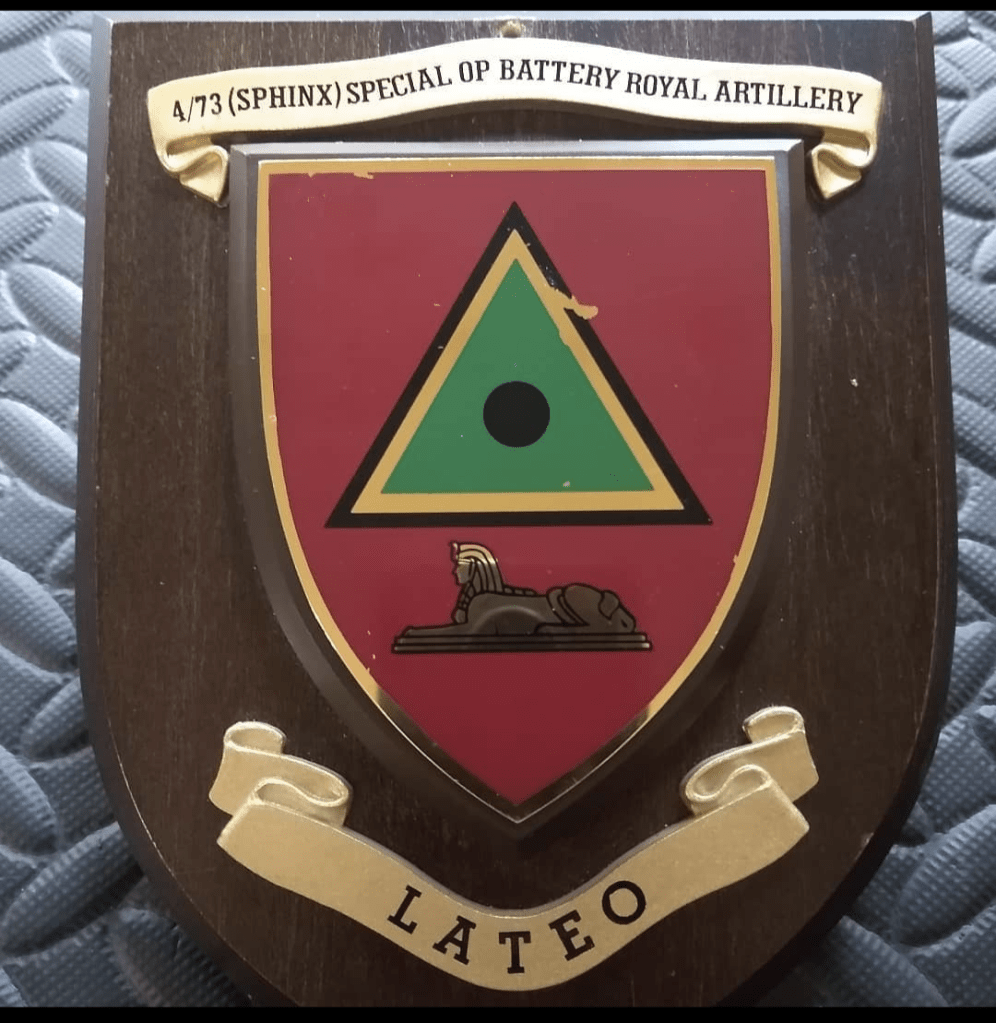

The Special OP Badge

“Here again, many in the Gunner hierarchy saw no need for any additional recognition for the special observers and were lacklustre in their support.”

The origin of the Special Observer badge does not seem to have been covered in the podcasts. Yet, it is an interesting story, and one that needs to be told. It had been decided early on (about 1983) that successful candidates who became Special Observers needed some form of recognition. This was to help recruiting, foster esprit de corps and dovetail with the HAC’s policy of issuing black lanyards to troopers who had passed the HAC SSC. However, there was much soul searching and teeth pulling that accompanied this rather straightforward requirement, from both the army establishment, from the RA and from within the Troops themselves.

I recall in 1985, WO2 Rocky Eyres coming to my office to inform me that he, and Geordie Watson, had designed the badge. It was, as was Rocky’s style, presented to me as a fait acompli. I stared at the design before me and, as if to give it more authority, Rocky declared that 50 plaques were, at this very moment, on their way from Singapore. I eyed Rocky for a while, and sensed Geordie Watson lingering outside my office door, their demeanour led me to assume it was a wind up. It wasn’t. What stared back at me from the page on my desk was a skull, superimposed with crossed Kalashnikovs, what looked suspiciously like SAS wings crowning it and the underside scroll with the immortal words “We Shall Not Be Found Out”. “Well,” I responded, holding Rocky’s piercing gaze, “you had better ring Singapore and cancel the consignment”.

He did, and the matter of the badge lay dormant for a while. HQ DRA, who had responsibility for, amongst other things, our equipment was also the regimental point of call for dress and, ipso facto, the badge. Here again, many in the Gunner hierarchy saw no need for any additional recognition for the special observers and were lacklustre in their support. I have to add here that there was an equipment procurement officer (I cannot recall his name) within HQ DRA, who was hugely supportive and procured a large amount of our early equipment. He worked hand in glove with the Troop Commander in the 32 Heavy Regiment Troop. While 5 Heavy Regiment had responsibility for policy and recruiting of the regular RA SBOP concept, the 32 Regiment Troop took the lead on deployment and equipment.

The CO of 5th Regiment, the Battery Commander of Headquarters Battery and I discussed some ideas and options on a few occasions. Then one day in early 1986 the Troops (from 5 and 32 Heavy Regiments) were both deployed near the IGB when I received an HF radio message to the Command Post (CP) telling me to ring the Regimental Headquarters at Dortmund immediately. It transpired that the staff officer at HQ DRA was on the cusp of missing the deadline for the submission of the badge design to the Army Dress Committee. A Committee that sat all too infrequently as far as I could recall. We had to get something to Woolwich by 4 pm that day. I drove to a number of local German Gaststubes (café/restaurant) before I found one with a phone and fax that we could use and began to receive and fire back, badge suggestions. In the end we settled on an earlier design – the standard OP symbol with a black border and black cannon ball. The Specialist Observer badge was born. It was, surprisingly, to take another 5 years for it to be approved and distributed. Such was the sensitivity to badges within the British army.

I heard Tony Stone mention in his podcast that the cannon ball was offset to indicate that the wearer was a ‘special’ individual. Our design and then one submitted to the Army Dress Committee had the ball slap centre. However, I recall that some prototypes were made by a German company in Dortmund (I think) and these had the ball off-centre, but this was never the intention. Perhaps this is the source of this misunderstanding. Finally, it is worth mentioning that the original troop plaques had the triangular Specialist OP badge in the centre of a shield, divided in half diagonally with RA red and blue on either side.

A lightning bolt ran across the diagonal and around the triangular badge to signify the communications requirements of the role. Underneath was the word ‘LATEO’, which is Latin for to be hidden, or some such thing. This was the brain child of one of the troop soldier’s wives who, if I recall, was a dental assistant. LATEO has stood the test of time, and in view of the propensity and nature of the many ‘Lawfare’ suits against the British army in recent years, “We Shall Not Be Found Out” would, perhaps, not have been the best motto for the Troop/Battery to have adopted!

Nick Lipscombe MSc FRHistS served for 34 years in the British Army; seeing considerable operational duty with the British and American armies. During the Cold War was a Troop Commander in the Special OP Troop from January 1985 to December 1987 where he was the officer commanding stay behind patrol operations.

An accomplished historian, author and lecturer. His first book, An Atlas and Concise Military History of the Peninsular War was published in 2010 and was selected as the Daily Telegraph (History) Book of the Year. He is recognised as a world authority on the battles and battlefields of the Iberian Peninsula and Southern France. In 2020 he completed his second major historical work, the Atlas and Concise History of the English Civil War 1639-51, which was selected as a runner-up for the Templar Medal. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Historical Society in 2015.

He is a tutor at the University of Oxford, Department of Continuing Education and an active member of numerous historical societies.

Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved by the Unconventional Soldier blog. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing of the author.

Excellent article and provision of really great background historical information. Thanks and regards Nick!

LikeLiked by 1 person

To answer some of the questions you guys raised on Ep45.

A main reason why enemy freqs aren’t jammed is for the J2 that can be gleaned from them such as content and DF; a reason why ECM is disliked in an EW environment. Jamming is an active EW measure and is putting a lot of energy down on specific frequencies so essentially a transmission in itself, which can be DF’d. Adversary forces can DF the jammer, call in a strike/fires and cause a devastating blow to the commanders intelligence gathering capabilities, another reason why passive measures are preferred.

To answer the COMSEC question; most NATO SATCOM radios now such as the Harris AN/PRC 117 G/F use modulation methods such as Frequency Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS) and Direct Sequence Spread Spectrum (DSSS). FHSS is as you guys alluded to a preset of frequencies that the radio can transmit on, which are cycled through within micro/milliseconds negating DF on certain freqs. DSSS is a wideband signal that sits in the within the noise floor making it very hard to detect for adversary EW. Combine these two with good COMSEC drills such as transmission time, radio silence periods, encryption etc it makes them very hard to detect.

Speaking from experience from a previous role. One specific ground based ISTAR asset within the British Army that works at reach from friendly forces at the FLOT or beyond, currently have a plethora of comms kit available for use, such as the MMR, PRC 117, PRC 152 and BOWMAN HF and VHF sets. Weight is obviously an issue which dictates to what can realistically be taken and how for long. For light role, it is generally SATCOM with HF in reserve.

Hope this answers some of your points. Anymore questions or further detail just hit me up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers for that additional info. Much appreciated.

LikeLike